Being a Counselor Activist

I was outraged from an early age. They say if you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention, so I guess I was paying attention. In 8th grade I protested my Spanish teacher who insisted that even the Mexican and Guatemalan kids in our class speak Spanish with a Castilian lisp, asserting that it was the “correct” way to speak. In 9th grade I protested inhumane treatment of animals, deforestation, and the fast food industry after watching the documentary film, “Diet for a New America,” based on the book by Baskin-Robbins heir, John Robbins. By the time I got to college I identified as an eco-feminist and volunteered as co-editor for the Humboldt State University Women Center “Zine.” We wrote articles about the wage gap, the Taliban and the Pro-Choice movement. That was in 1997. Twenty years later, it seems we are still fighting the same fight. Different leaders, same dogma.

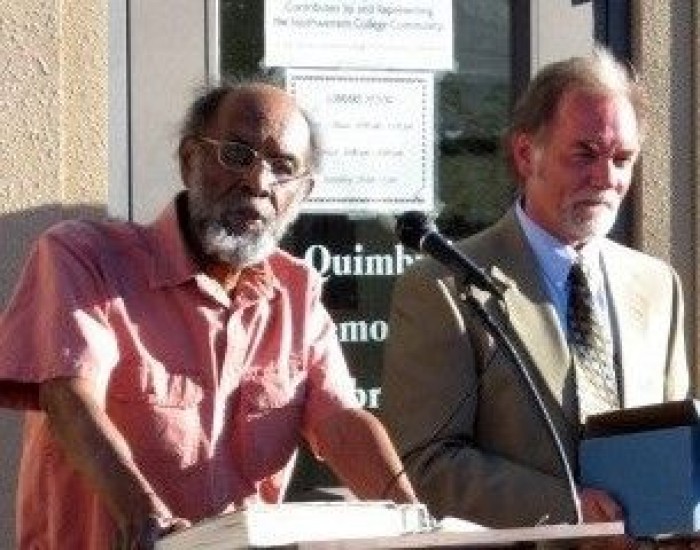

At Southwestern College I had the good fortune to take “Multicultural Issues in Counseling” from a professor named George Tate. George passed away a few years ago, but at the time he was a spry octogenarian with twinkling eyes and a beard that reminded me of my granddad. George was a minister, a social worker, and an activist who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960’s. He told us that being a counselor is a great way to help folks cope with a broken system, but that we must also recognize that when a system oppresses, exploits or otherwise harms the individual, we also have an ethical responsibility to work to change that system. He taught us that being a counselor means that you also have to be an activist.

Tate. George passed away a few years ago, but at the time he was a spry octogenarian with twinkling eyes and a beard that reminded me of my granddad. George was a minister, a social worker, and an activist who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960’s. He told us that being a counselor is a great way to help folks cope with a broken system, but that we must also recognize that when a system oppresses, exploits or otherwise harms the individual, we also have an ethical responsibility to work to change that system. He taught us that being a counselor means that you also have to be an activist.

Birmingham, Alabama born civil rights organizer, writer, and scholar, Dr. Angela Davis, is famously quoted for saying, “I no longer accept the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.” With this critique of the well-known serenity prayer, which reads “Lord grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference,” Dr. Davis calls upon us all to challenge the status quo and refuse to lay down in defeat just because a problem seems too big or too impossible.

Acceptance, along with forgiveness, are central teachings of many spiritual pathways, but when do we accept things as they are, and when do we work to create systemic change? Are those two things exclusive or can we do both at the same time? Katherine Ninos, Vice President of Southwestern College for more than two decades and creator of SWC’s unique “Consciousness” curriculum, says that to be a true agent of change, we must be willing to “stand in our truth,” even when it means being in opposition to the powers that be–even when it means putting ourselves in danger. She has been known to say, “They can only kill your body,” to remind us that our spirit, in service to a cause, is much bigger in comparison.

But isn’t it this spirit-in-service-to-a-cause thing that brings about war and conflict all over the world? Wasn’t the founding father’s commitment to our young nation and “Manifest Destiny” used to justify the demise of an entire continent full of indigenous peoples? Is what fuels humanitarian leaders the same thing that fuels suicide bombers? What happens when the righteous fall into self-righteousness and lose track of the true purpose behind their desire for change? Can violence ever be justified as a means to an end?

I love that my education at Southwestern invited me to grapple with these kinds of questions. They are the same questions that many of my clients and students struggle to answer. For my part, all I truly know is that when I dance in a One Billion Rising Flashmob, march to protect the rights of women, or send a donation to a local non-profit agency, I feel a sense of solidarity with the collective and I trust that the work of the collective is ultimately in service to the evolution of human consciousness on the planet.

–Kate Latimer, MA, LPCC, SWC Class of 2007

Southwestern College Santa Fe, NM

Southwestern College Santa Fe, NM